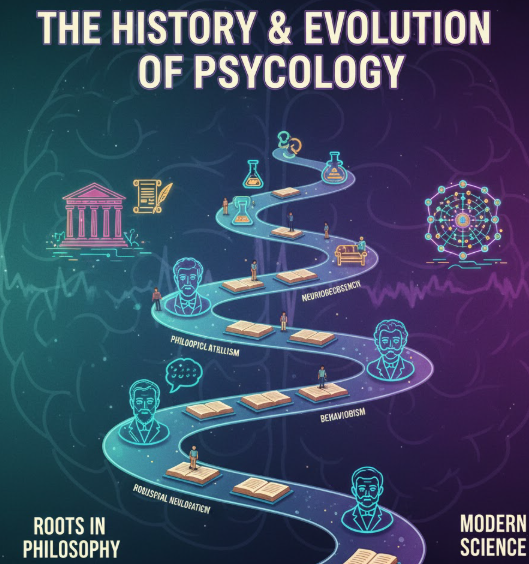

Psychology did not appear overnight as a science. It evolved slowly—through centuries of questioning, observation, debate, and refinement. What we now call modern psychology is the result of a long journey from philosophy to laboratory science, and finally to an integrated, evidence-based discipline.

Understanding this evolution is important because it explains why psychology studies the mind the way it does today.

1. Philosophy: The Pre-Scientific Era

(Before the late 1800s)

Before psychology became a scientific discipline, it existed as philosophical inquiry. Thinkers were deeply interested in questions about the mind, behavior, consciousness, and human nature—but they relied on reasoning, not experimentation.

Ancient Greece

Some of the earliest ideas about the mind came from Greek philosophers:

Socrates emphasized self-reflection and rational thinking.

Plato proposed mind–body dualism, arguing that the mind (or soul) is separate from the body and immortal.

Aristotle believed the mind originated in the heart (biologically incorrect), but he made systematic observations about memory, learning, perception, and emotion. His work laid early groundwork for studying behavior.

Although many of these ideas were scientifically inaccurate, they were important because they treated the mind as something worth studying.

Medieval and Renaissance Thinkers

René Descartes (17th century) famously stated, “I think, therefore I am.”

He reinforced mind–body dualism, suggesting the mind and body interact but are distinct.

His ideas influenced later scientific thinking, especially in neuroscience and psychology.

Key Point of This Era

Psychology existed as questions and theories, not experiments.

There were no laboratories, measurements, or controlled studies—only philosophical reasoning.

2. Psychology Becomes a Science

(Late 1800s)

The true birth of psychology as a scientific discipline occurred in the late 19th century.

Wilhelm Wundt (1879, Germany)

Founded the first psychology laboratory in Leipzig, Germany in 1879.

Known as the father of experimental psychology.

Used introspection, where trained participants described their conscious experiences under controlled conditions.

This moment is widely recognized as the official beginning of psychology as a science.

Structuralism – Edward Titchener

A student of Wundt.

Aimed to break conscious experience into basic elements, similar to how chemistry breaks matter into atoms.

Focused on sensations, feelings, and images.

Limitation: Introspection was subjective and difficult to verify scientifically.

3. Functionalism

(Late 1800s – Early 1900s)

As a response to structuralism, functionalism shifted focus from what the mind contains to what the mind does.

William James (United States)

Known as the father of American psychology.

Influenced by Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution.

Asked:

Why do we think the way we do?

How do mental processes help us adapt and survive?

Functionalism emphasized real-world application and influenced education, work psychology, and applied research.

4. Behaviorism

(Early 1900s)

Behaviorism marked a dramatic shift in psychology.

Instead of studying thoughts or feelings, psychologists focused only on observable behavior.

Key Figures

John B. Watson

Defined psychology as the scientific study of behavior.

Rejected introspection and mental explanations.

B. F. Skinner

Developed operant conditioning.

Demonstrated how behavior is shaped through reinforcement and punishment.

Behaviorism made psychology more objective and measurable, but it largely ignored internal mental processes.

5. Psychoanalysis

(Early 1900s)

At the same time behaviorism was rising, another powerful approach emerged.

Sigmund Freud

Emphasized the unconscious mind.

Believed behavior is shaped by:

Childhood experiences

Unconscious conflicts

Dreams and hidden desires

Introduced the concepts of:

Id

Ego

Superego

While Freud’s work was influential, many of his theories lack strong empirical support and are considered historically important but scientifically limited today.

6. Humanistic Psychology

(1950s–1960s)

Humanistic psychology emerged as a reaction against both behaviorism and psychoanalysis.

Key Figures

Carl Rogers

Developed client-centered therapy.

Emphasized empathy and unconditional positive regard.

Abraham Maslow

Proposed the hierarchy of needs.

Focused on self-actualization and personal growth.

Humanistic psychology emphasized free will, meaning, and human potential, influencing counseling and therapy practices.

7. The Cognitive Revolution

(1950s–1970s)

Psychology returned to the study of the mind—but this time with scientific rigor.

Key Contributors

Jean Piaget – cognitive development in children

Noam Chomsky – challenged behaviorist explanations of language

Psychologists began studying:

Memory

Attention

Perception

Thinking

Problem-solving

This movement laid the foundation for modern cognitive psychology.

8. Modern Psychology

(Late 20th Century – Present)

Today, psychology is an integrated and multidisciplinary science.

Major Branches

Clinical psychology

Cognitive psychology

Social psychology

Biological psychology

Industrial–Organizational psychology

Neuropsychology

Modern Tools

Brain imaging (fMRI, EEG)

Neuroscience

Artificial intelligence

Big data and computational modeling

Modern Focus

Understanding the mind and behavior:

Scientifically

Practically

Ethically

Conclusion

The history of psychology shows a steady movement:

from philosophical questioning,

to experimental science,

to modern, evidence-based understanding.

Each era—despite its limitations—contributed something essential. Modern psychology stands on these foundations, combining biology, cognition, behavior, and social context to understand what it truly means to be human.

This evolution reminds us that psychology is not fixed—it continues to grow as our tools and understanding improve.